The Lancet is a heavyweight medical journal – one of the world’s most influential and highly cited. It uses its political heft to make global challenges part of the remit of medical science. In recent years, it has published scientific reviews (called ‘Commissions’) on Migration, on Sexual and Reproductive Rights, on the legal determinants of health and on Poverty.

But The Lancet’s most important interventions have been in the area of environmental and climate change. It established Commissions on Planetary Health (2015), Food in the Anthropocene (2019) – and Climate Change (2009 and 2015). The publication of The Lancet’s 2015 Climate Change Commission was timed for the run-up to the 2015 Paris Agreement. A landmark in global climate governance, the Paris Agreement puts people at the centre of its case for action. It acknowledged that climate change is ‘an urgent threat to human societies’, requiring global action to keep the increase in global temperatures below critical thresholds at which the human threat becomes uncontainable.

Lancet Countdown on health and climate change

To ensure its 2015 Climate Change Commission was not left on a shelf to gather dust, The Lancet set up a ‘Countdown’ process to track the changing health impacts of climate change and whether and how governments and industry were taking action. It published Countdown reports in 2017, 2018 and 2019.

And now the 2020 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change is out. In line with previous Countdown reports, it focuses on the human dimensions of climate change, a focus that connects directly with the CAST Centre.

In this blog, we outline what the Lancet Countdown covers and highlight findings from the 2020 report relevant to CAST’s agenda. Hilary Graham, Pete Lampard and Stuart Capstick are among the authors of the 2020 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change.

The Lancet Countdown tracks global indicators of health and climate change using global and publicly-available data. This includes the direct impacts on health – for example, the relentless increase in exposure to extremes of heat and in heat-related deaths and the spread of climate-sensitive diseases like dengue fever and malaria. Along with indicators of health impacts, the Countdown report tracks investments in adaptation and health resilience as well as mitigation and its health co-benefits. An important section of each report tracks the economic costs of climate change and the transition to a zero carbon economy. For example, the 2020 report provides evidence on loss of earnings from climate-related extreme events (hitting low-income countries hardest) and the continuing subsidy of fossil fuel industries. More positively, it tracks trends towards fossil fuel divestment and employment in the renewable energy sector.

Public and political engagement in health and climate change

Of particular relevance to those interested in how climate change is being represented, communicated and understood by society at large, the Lancet Countdown includes a focus on public and political engagement in health and climate change. It monitors engagement by the media, by individuals, by the research community, by governments and by the corporate sector. These indicators are important for assessing the ways in which the links between climate change and health are receiving attention around the world.

One indicator is tracking newspaper coverage of health and climate change from 2007, the year before the 2008 WHO World Health Assembly where member states of the UN made a multilateral commitment to protect human health from climate change. Using multi-language databases (Lexis Nexis, Proquest and Factiva), together with the Chinese language edition of the People’s Daily, the report provides evidence on newspaper coverage across the world. The coverage of climate change and health has now reached its highest recorded level. Analysis of the levels of media coverage are complemented by content analysis of reporting in two US newspapers (the New York Times and the Washington Post) and two in India (the Hindustan Times and the Times of India). This has revealed that a dominant theme in reporting has been of the health impacts of climate change, followed by reference to the common causes and co-benefits of climate change, especially in the context of air pollution.

For individual engagement, the report uses the digital footprint of users of Wikipedia, the world’s largest encyclopaedia. Engagement is measured by visits to pairs of articles, for example, clicking from a page on human health to one on climate change (‘co-clicks’). Such engagement has increased over time, with spikes in engagement coinciding with key events in climate politics. For example in 2019, co-clicks spiked during the 25th UN Conference of Parties and at the time of Greta Thunberg’s speech at the UN’s Climate Action Summit in September.

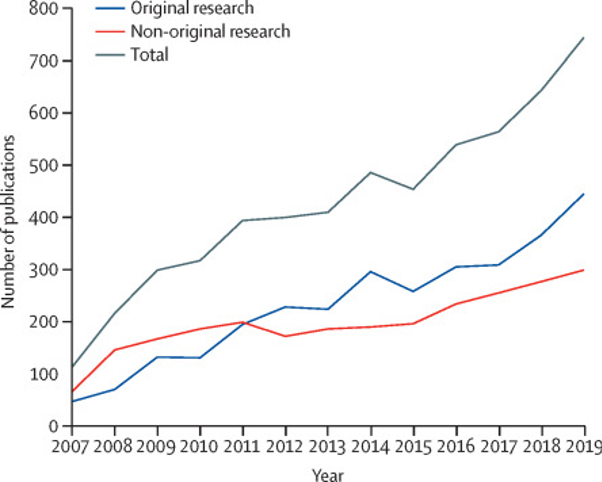

Scientific engagement in health and climate change is monitored through analyses of coverage in scientific journals. In line with trends in media coverage, scientific coverage is now at its highest recorded level. The trend is evident both in original research (primary studies and evidence reviews) and research-related articles (editorials reviews, comments and letters), as the Figure below illustrates.

Government engagement is tracked in two ways. The first is through analyses of the United Nations General Debate, the forum at the annual UN General Assembly at which national leaders speak directly to the global community. At the 2019 forum and speaking for the USA, Donald Trump failed to make a single reference to climate change (let alone to links between climate change and health). In contrast and as in previous years, it is poorer and climate-vulnerable countries, particularly Small Developing Island States, that continue to urge global leadership on protecting human health from climate change. The second indicator looks at engagement in the National Determined Contributions which form the backbone of the 2015 Paris Agreement. The 2020 report describes how – again – it is low-emitting and low-income countries that are highlighting the links between climate change and health. Their NDCS include frequent references to extreme weather events (e.g. floods and droughts) and food insecurity and the devastating impacts on people’s lives.

The Lancet Countdown: findings in a nutshell

Putting the evidence from the Countdown reports together, two broad themes stand out.

Firstly, the health costs of climate change are multiplying and no country is immune. It is widely recognised – by politicians and public alike – that climate change is human in its origins. It is now increasingly evident that it is human in its impacts.

Secondly, societal actors are highlighting these human impacts. Health and climate change is an increasing focus of research; the links are increasingly covered by the media, and individuals are seeking out information for themselves. This is putting a human face on climate change: in science, in the media and in public debate. It is a human face in which inequalities are deeply etched. As evident in the indicators on UN engagement and the NDCs, engagement in health and climate change is led by countries that are affected most by a changing climate to which they have contributed least. At the same time, the science of health and climate change continues to be led by high-income countries whose wealth derives from high-carbon and health-damaging industries.

As this suggests, the Countdown’s coverage of the societal causes and consequences of climate change is closely aligned with CAST’s focus on societal transformations – with finding ways to live differently and better. The Countdown report emphasises that action on climate change can lead to cleaner skies, healthier diets, and safer places to live. While located within the medical and social sciences respectively, the two initiatives share common perspectives and values. Like CAST, the Lancet Countdown is part of a global movement to put people, communities and organisations at the heart of climate action.

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)32290-X/fulltext#seccestitle840