This piece was originally published by Business Green and is reproduced here with their permission.

Recent headlines that the UK government might slap a carbon tax on burgers and the great British banger have reignited controversy about what tackling the climate will mean for our food. The rumours of an imminent meat tax were dismissed by the PM in a grilling by The Sun’s new Green Team, but the fundamental question remains of what climate change means for our diets.

As public concern about climate change continues to grow, undented even by COVID-19, how do policy-makers square the strength of public support for affordable meat and British farmers with less palatable national climate targets that may soon impact everyday choices for families?

Why not ask a representative sample of the British public themselves? That’s what Parliament decided when six of its committees commissioned the first-ever UK-wide climate assembly, 108 everyday people who gave up six weekends last year to learn about the issues and wrestle with policy trade-offs consistent with the UK’s 2050 climate targets.

After hours of expert presentations, including from the NFU, input from their fellow assembly members, and intense discussion the 35 diverse assembly members charged with looking in detail at what we eat and how we use our land drafted their recommendations. They include a strong emphasis on support for farmers, producing and buying more food locally, and measures to incentivise a voluntary change in our diets, reducing meat and dairy consumption by 20-40%. They also stress that lower carbon and more local diets need to be affordable for all.

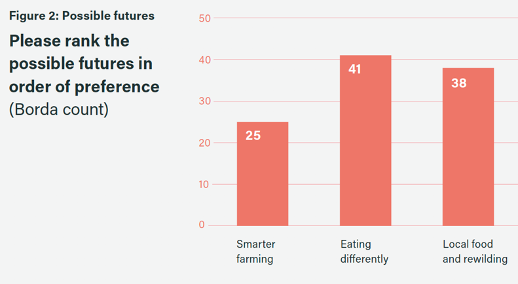

Climate Assembly members discussed three possible ‘futures’ for food and land that would reach our net zero targets and voted on their preferences:

- ‘Smarter farming’ in which farming becomes more efficient and uses more land to store carbon, but consumers do not change their behaviour (i.e., no reduction in meat or dairy);

- ‘Eating differently’ in which farmers, retailers and individuals take steps to reduce food waste and choose lower-carbon foods – this includes people eating 20% less red meat and dairy; and

- ‘Local food and rewilding’ involving fundamental change in food systems and landscapes, towards local food production and more space for biodiversity – including people eating at least 40% less red meat and dairy.

Assembly members’ clear preferences were for the ‘Eating differently’ and ‘Local food & rewilding’ futures (see first Figure), with ‘Smarter farming’ lagging some way behind. As votes were fairly evenly split between ‘Eating differently’ and ‘Local food & rewilding’, we say in the report that assembly members supported a 20-40% reduction in red meat and dairy. We also emphasise assembly members’ preference for this change to be voluntary, backed by significant education, product labelling, and incentives for choosing low-carbon foods.

The latest advice from the UK government’s climate advisors, the Climate Change Committee, is in-line with the assembly’s recommendations. It says that to reach our emissions targets, we need to cut red meat and dairy consumption by 20% by 2030 and more in later years. Red meat and dairy products generate more greenhouse gases than most other types of food, so cutting down on these foods can help reduce emissions as well as improve our health.

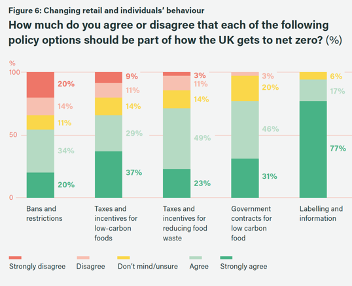

Consistent with their preferences for other areas, like travel and home energy use, assembly members wanted consumers and citizens to be actively involved in the transition to a low-carbon society and to ensure it was fair and affordable. Importantly, the reasons they gave for supporting these food futures over one in which there was no change on the consumer side, included the health benefits of a low-carbon diet, financial benefits of cutting food waste, biodiversity benefits of reduced livestock farming, and benefits for communities and farmers of people producing and buying products more locally. In terms of policies to achieve these net zero food futures, assembly members were most in favour of better information and public procurement, and least supportive of regulations (see second Figure).

This support from the Climate Assembly for changing diets to help tackle climate change should not surprise us. Recent opinion polls show similar support from the public for cutting meat consumption to reduce emissions. One UK survey in October 2020 found 70.2% now agree we should definitely/probably reduce meat products in our diets in order to tackle climate change, albeit a more modest 54.2% agree we should definitely/probably reduce dairy products in diets. The interim findings of Scotland’s Climate Assembly last month also indicate popular support for encouraging less meat and dairy in diets.

These proportions supporting dietary change have steadily risen since previous surveys, in line with changing consumer preferences. Indeed, the range of vegan and vegetarian foods available on the high street has expanded massively, and food manufacturers are focussing investment in this area. During lockdown, people experimented more with plant-based foods, fuelling an already huge growth in consumer demand for vegan products in the last couple of years. Global brand Unilever, for example, expects its sales of plant-based products to grow five-fold in the next 5-7 years.

This rise in demand for plant-based, low-carbon foods is not a result of any government intervention but of growing concern about health and sustainability and an interest in where our food comes from and how it is produced. Governments can support this trend by better labelling and education, and by policy nudges like making low-carbon foods more affordable and available (e.g., in schools and hospitals), in line with Climate Assembly UK recommendations.

Despite media headlines warning ‘Hands off our sausages’, Climate Assembly UK shows policy-makers that most people want a persuasive ‘carrot rather than stick’ policy approach to encourage the uptake of lower carbon food.

In the year that Britain hosts the UN climate talks in 2021, the government is right to explore global leadership in tackling climate change across every sector of its economy. While UK leaders may have previously been concerned that low carbon behaviour might be politically unpalatable, they now have strong evidence that most people are firmly behind ambitious climate action.

Climate Assembly UK shows better public engagement and public information must be at the heart of the behaviour changes needed for the UK’s low carbon transition. In critiquing the government’s Covid-19 public information campaigns, veteran ad man Rory Sutherland explains, “No-one likes a nanny state, but there is nothing wrong with a helpful state.” Understanding this difference will be vital if the UK is to achieve national Net Zero targets by 2050.

See more: Max, a 17 year old participant in Climate Assembly UK, talks about the experience of discussing the role of food in climate action as part of the assembly. Click here to watch.